Sunday Stories: George Arnold and the Post Office

Excerpted from: One Hundred Years on the South Loup

Since 1876, mail destined for this part of the Loup valley

was brought by horseback every two weeks from Plum Creek and addressed “Arnold

& Ritchie Ranch, c/o Postmaster.” The partners had taken turns handling the

mail – now a change would have to be made. Allen offered to have the post

office in his sod house and on March 21, 1881, he, with Landis Correll and

George Arnold, met to choose a name for the new office. “Correll” was

considered, so was “Allen,” finally “Arnold” was chosen and a letter sent off

to Washington for a new rubber stamp.

George Arnold, partially paralyzed from a stroke suffered

the year before, probably never knew the little office given his name ever

developed into a town. He went back to the family home in Ohio, where he died

in 1900, leaving no relatives in Arnold. Later residents by the same name had no

connection.

Before entering the cattle business, Arnold had served in

the Civil War and married Ella Taylor, daughter of Edward Taylor, editor of the

Omaha Bee and one-term governor of the state by appointment. The Arnolds had

four children, one a baby when they came to the ranch - the only baby in the

country.

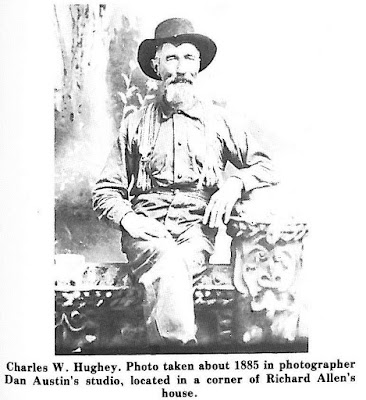

Charles W. Hughey, cowboy, cook and general handyman, came

up the Loup with cattlemen San Ritchie and George Arnold, in 1877, and worked

for them and other ranchers. He was a familiar sight around the country, riding

his horse, Redbird, followed by two black dogs. It was “Grandpa” or “Uncle”

Hughey, as he was called, who discovered the body of the trapper frozen in

Powell Canyon. When Arnold and Ritchie left the country in the spring of ’81,

they sold the 320 acre ranch headquarters to Hughey. Soon after he moved into

the log cabin, it caught fire and was hastily pulled down to save the red cedar

logs. It was from this land Hughey, in 1884, donated a small plot to be used as

a cemetery, when Dora, the small daughter of miller John Koch, died.

Hughey himself was soon buried there, killed in 1893 when a

hay knife pierced his chest in a fall from a hayrack. His grave can be seen

along the cemetery’s west fence, with its headstone engraved as being a gift from

the town of Arnold. His wife had died before he came to Arnold, but G. J.

Hughey, in Arnold in 1883, may have been his son.

By early summer, would-be settlers were coming in a steady

stream. The Custer County Republican reported: “A gentlemen from over on the

South Loup informs us that from Sunday afternoon until afternoon of the

following day he counted fifty-two teams – land hunters – heading for the head

of the Loup.”

Homeseekers coming up the dusty river valley would camp near

the Allens for a few days or weeks, while their men scouted out the surrounding

country and stepped off 160 acres in places that would be called Powell Canyon,

Yucca Valley, Mills Valley, Kilmer Valley, Milldale, Cedar Grove, Loyal and

Pleasant Hill.

Not all who came, of course, filed on land, and of those who

did, many could not take the hardships, or starved out before proving up,

leaving the claim open for the next comer. A survey done years later showed an

average of two and a half filings on each quarter in Custer County.

There were three ways of acquiring public land. The

Homestead Act of 1862 gave 160 acres to the head of a household who would live

on it for five years and make certain improvements; the Preemption Act of 1841

gave 160 acres to any man who would live on it, erect a dwelling and after

proving up, pay the government $1.25 an acre. It was possible for him to

preempt an adjoining quarter at the same time he was homesteading another.

The third way was by the Tree Claim Act (Timber Culture Act) passed in the early

1870s, giving 160 acres to a settler who would plant 40 acres of trees and

cultivate them for eight years. These requirements were later reduced, but even

still, were impossible to fulfill due to natural conditions. The act failed in

its intentions to forest a barren land and was repealed in 1894, but for a

time, it was possible for an ambitious settler to gain title to 480 acres of

public land.

Allen added a tree claim to his holdings later and wrote in

1936: “Most men on tree claims allowed the weeds to grow as high as the trees

and they never had a chance. I think that is why we see so many dwarfed patches

of underbrush around Arnold today.” He had attacked the problem of lack of

trees the first summer by setting out the fine grove that would furnish shade

and shelter for almost eighty years. The last of these trees were taken out a

few years ago to make room for the swimming pool.

Comments

Post a Comment